Daniel 5

The Writing on the Wall

The Writing on the Wall

Comparative commentary by Michelle Fletcher

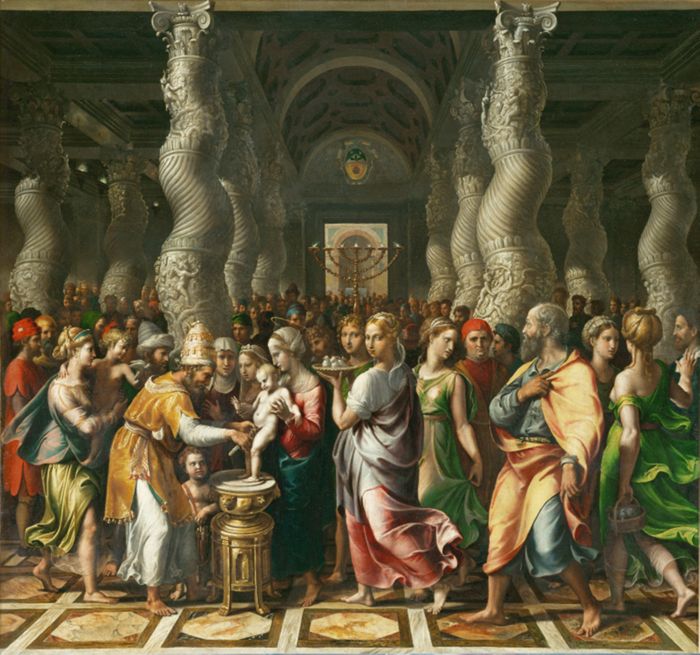

Michelle Fletcher: The writing’s on the wall. Something bad is going to happen. We know that. But Daniel 5 is the place where this all started. It’s a story of a king: King Belshazzar. He’s having a feast with a thousand of his lords, and he asks for the implements from the temple in Jerusalem to be brought. And he, his wives, his concubines, and his guests drink from them. And they praise the gods of stone and wood. And what happens? The fingers of a human hand appear and they write on the plaster of the wall opposite the lamp. The King doesn’t know what it says. What is this strange writing? He summons his wise men, but they can’t read the writing or tell the interpretation either.

And it’s this moment that we find in Rembrandt’s rendering of this scene. Rembrandt has shown the moment of ultimate terror for the King.

He’s looking at the wall and he doesn’t know what it says. Everybody is transfixed by the writing, but what does it say? Well, Rembrandt has given us an enigma.

At this time in Amsterdam when Rembrandt painted this work, somewhere between 1636 and 1638, we know that there was a Portuguese rabbi living there called Menasseh ben Israel. And Menasseh ben Israel published a work saying that the writing was not read as the Aramaic traditionally was, from right to left. Instead, the writing reads top to bottom, and we can see Rembrandt following this form in his painting. If we look in the Aramaic, it says, reading top to bottom, right to left, mene, mene, tekel, upharsin. And we know that these are the words that Daniel, when he is brought in to tell the King what the words say, reads on the wall. But Daniel hasn’t been brought in yet in Rembrandt’s rendering. A totally different moment, or way of thinking about this scene, appears in John Martin’s painting.

Gone are cryptic words. Instead in the top left we have the writing stretching out on the wall in characters unreadable to everybody.

But what the writing tells us is going to happen is clear. Something terrible is happening. Stretching out in amazing architectural precision, we see the city of Babylon. We see Daniel as the centralized figure brought to tell the King the message. Not just to read the writing, but say the explanation of the writing. And Daniel in the text, when he is brought before the King to read the writing, explains in a very free interpretation, translation, what mene, mene, tekel, upharsin means.

He says: ‘mene’—your days have been counted and your kingdom is coming to an end. ‘Tekel’—you have been weighed and found wanting. And then a pun, ‘peres’—your kingdom will be divided between the Medes and the Persians; a pun with peres on Persians. It’s a free translation using passive forms of the verbs. But what we can see in Martin’s rendering is what this means. Destruction is here. It is happening now. And as the text tells us at the end of the chapter, Belshazzar that very night is killed and his kingdom given away. And this is undeniable in Martin as we see the tower falling down, ready to fall upon the people. But what if we press the pause button before this destruction, and we move into the work of Susan Hiller.

There’s something about this vision of unreadable writing that gets forgotten. It is unreadable. We know it spells destruction, but what if we take it back before we know what it says? Susan Hiller’s installation, 1983–84, takes us into the domestic; the strangely familiar, the unheimlich, the un-homely, the unsettling, the world of the uncanny. In her installation we see at the centre a television, and playing on the television is a looped video of a fire. And spoken over the fire are three different sections of the video. One: strange unworldly singing. Two: Hiller’s son Gabriel struggling to remember the story of Daniel, and also an experience of looking at Rembrandt’s painting. And finally, reports found in newspapers where people fell asleep in front of the television and awoke after the programmes had finished (back in the day where TV didn’t go 24 hours) and they saw people on the television. And where’s the writing in this? The title of the installation is Belshazzar’s Feast, the Writing on Your Wall. And in the installation we see twelve different portraits, or pictures, that Hiller has taken of herself in photobooths, and then she’s inscribed over the top automatic writing. Automatic writing is a process that is often associated with the feminine, spiritualism. It was also central to the Surrealists, in the sense of finding the inner muse. Hiller positions herself between these ideas; writing that comes from within that can’t be read. [10:45] She gives us no translation. In our twenty-first century we’re so used to being literate, to being able to read countless images, signs, words. How do we get back to knowing what it’s like to encounter something that cannot be read and translated? Hiller does that.

Daniel 5 is, in the end, a text about power. And the community that it was for are a community without power. In Daniel 5, the tables are turned. It’s the King who is out of power, out of control, in the position of unknowing. And in the end, that’s what the writing on the wall is about. It’s destruction. It’s doom. Something bad’s going to happen, but you don’t know what it is. And at the moment, you can’t read it. All you know is that there’s something out there you can’t explain.

Commentaries by Michelle Fletcher